I’m very proud to announce the completion of my first programming language compiler!

Malcc is an incremental and ahead-of-time lisp compiler written in C.

This is the story of my progress over the years and what I learned in the process. An alternate title for this post is: “How to Write a Compiler in Ten Years or Less”

(There’s a TL;DR at the bottom if you don’t care about the backstory.)

Successful Failures 🔗

I have dreamed of writing a compiler for nearly a decade. I’ve always been fascinated by how programming languages work, especially compilers. Though, I imagined a compiler as dark magic and understanding how to make one from scratch firmly out of reach for a mere mortal such as myself.

But that didn’t stop me from doing and learning!

First, an Interpreter 🔗

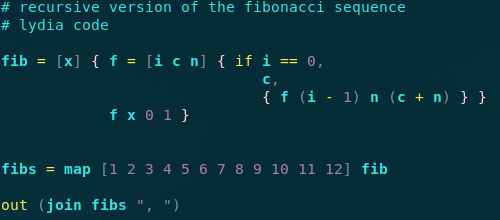

In 2011, I started work on a simple interpreter for a made-up language called “Airball.” You can tell from the name how much confidence I had in myself to make it work. It was a fairly simple program written in Ruby that parsed the code and walked the abstract syntax tree (AST). Once I realized it did kind of work, I renamed it Lydia and rewrote it in C to make it faster.

I remember thinking the syntax for Lydia was quite clever! I do still enjoy the simplicity of it.

While Lydia was far from the compiler I wanted to make, it was a small taste that inspired me to keep going. Though, I was still plagued by unanswered questions of how to make a compiler work: What do I compile to? Do I have to learn assembly language?

Second, a Bytecode Compiler and Interpreter 🔗

As a next step, in 2014, I started work on my scheme-vm – a virtual machine for Scheme written in Ruby. I thought using a VM with its own stack and bytecode would be a nice middle-ground between an AST-walking interpreter and a full compiler. And since Scheme is formally specified, I wouldn’t have to invent anything.

I tinkered off-and-on with my scheme-vm for over three years and learned a lot about how to think about compiling. But, in the end, I knew I couldn’t finish it. The code was becoming an unmaintainable mess and I still had a long way to go to completion. Without a guide or previous experience, I was mostly feeling my way around in the dark. It turns out that a language specification is not the same as a guide. Lesson learned!

By the end of 2017, I had shelved scheme-vm in search of something better.

Enter Mal 🔗

Some time in 2018 I happened across Mal, the Clojure-inspired Lisp interpreter.

Mal was invented by Joel Martin as a learning tool and has since gathered over 75 implementations in different host languages! I knew when I saw all those different implementations that I could learn a lot about the process – if I got stuck, I could go consult the Ruby or Python implementation for cheats. Finally, someone who speaks my language!

I also figured that if I could get through the steps writing an interpreter for Mal, I could probably repeat those same steps to make a compiler for Mal.

A Mal Interpreter in Rust 🔗

My first go was to follow the step-by-step guide and build an interpreter. At the time, I was also heavy into learning Rust (I’ll save that for another blog post), so I created my own implementation of Mal in Rust: mal-rust

I wrote a bit about my time using Rust here.

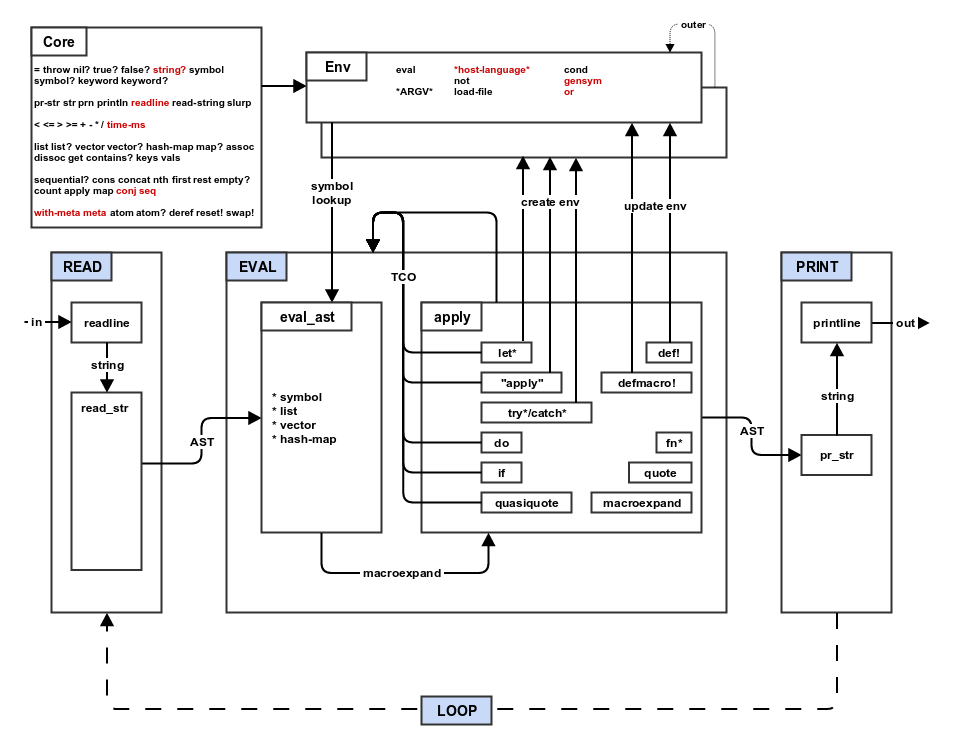

This was an absolute joy! I cannot give enough praise or thanks to Joel for creating the excellent Mal guide. It has detailed written steps, flowcharts, pseudocode, and tests! – everything a developer would need to make a programming language from start to finish.

By the end of the Mal guide, I was running the Mal implementation of Mal (written in Mal) on top of my Rust-hosted implementation of Mal. (2 levels deep, whew) I jumped on my chair in excitement when this worked the first time!

A Mal Compiler in C 🔗

Once I proved mal-rust to be a viable Mal implementation, I started researching how I could write a compiler. Do I compile to assembly? Do I dare compile directly to machine code?

I saw an x86 assembler written in Ruby which intrigued me, but the thought of working with assembly gave me pause.

At some point I happened across this comment on Hacker News, which mentioned using the Tiny C Compiler as a “compilation backend.” This seemed like a great idea!

TinyCC has a test file showing how to use libtcc to compile a string of C code from a C program. This gave the start I needed to build a “hello world” proof of concept.

Starting again with the Mal step-by-step guide, along with my stale C experience, I was able to build a Mal compiler in a couple months worth of spare evenings and weekends. The process was a joy.

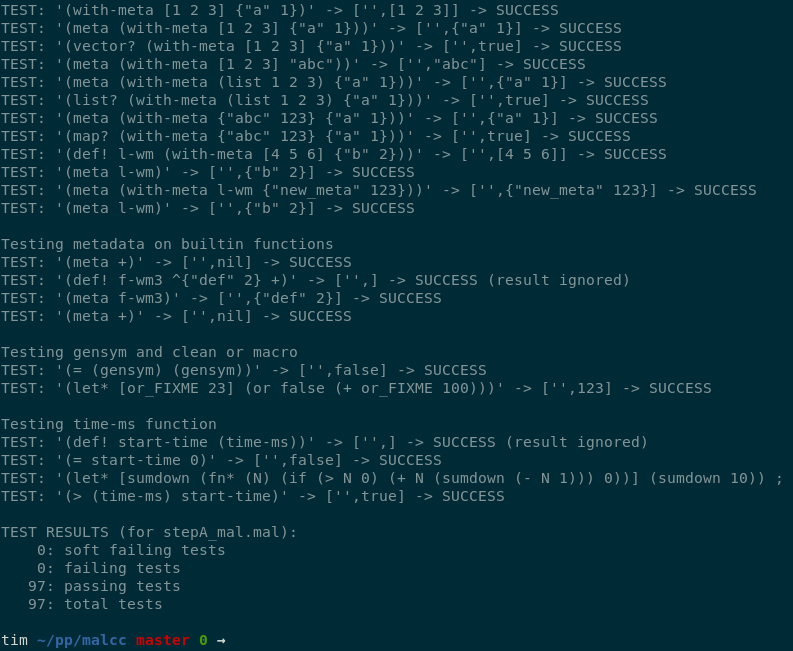

If you’re used to test-driven development, you’ll recognize how valuable having a pre-done test suite is. The tests will guide you toward a working implementation.

I can’t say much about this process, other than, again, the Mal guide is a treasure. At each step, I knew exactly what what I needed to do!

Tricky Bits 🔗

Thinking back, here are some tricky bits specific to writing a Mal compiler that I had to figure out:

Macros must be compiled on-the-fly during compilation and ready to be executed during compilation of the program. This is a little mind-bendy.

The “environment” (the tree of hashes/associative-arrays/dictionaries that holds variables and their values) needs to be present for both the compiler code and the resulting code for the compiled program. This is so that macros can be defined at compile time.

Since the environment is available at compile time, I originally had Malcc catching undefined errors (access of a variable that was not defined) at compile time, but this broke expectations of the Mal test suite in a couple places. In the end, I disabled that feature so I could get the test suite passing. It would be cool to add it back as an optional compiler flag though, since it could catch a great deal of errors ahead-of-time.

I compiled the C code by writing to three strings passed around in a struct:

top: top level code – functions are written heredecl: declarations – declaring and initializing variables used in the bodybody: where the main work is done

I spent a day thinking about writing my own garbage collector, but decided it could be an exercise for further learning at a later date. The Boehm-Demers-Weiser Garbage Collector is an easy drop-in library and is readily available on lots of platforms.

It’s critical to be able to easily see the code your compiler is writing. Anytime my compiler saw the

DEBUGenvironment variable, it would spit out the compiled C code so I could review the mistakes.

Things I’d Do Differently 🔗

Writing C code and trying to keep it indented was a bit of a pain and I wish I would have done something else. I believe some compilers write ugly code and then “pretty it up” with a library before writing it out. This is something to explore!

Appending to strings when generating code is a bit messy. I might consider building an AST and then converting that into the final string of C code. This should tidy up the code and give the compiler a nice bit of symmetry too.

Now the Advice 🔗

I love that it’s taken me nearly a decade to learn how to make a compiler. No, really. Each step along the way is a fond memory in my process of becoming a better programmer.

That’s not to say I’m “done” though. There are still many hundreds of techniques and tools I need to learn to feel like a real compiler writer. But I can confidently say “I did it.”

Here is the process I’d recommend to make your own Lisp compiler:

- Pick a language you feel comfortable in. You don’t want to be learning both a new language and how to make a language at the same time.

- Follow the Mal guide and write an interpreter.

- Rejoice!

- Follow the guide again, but instead of executing the code, write code that executes the code. (Don’t just “refactor” your existing interpreter though. Start from scratch. Copy and paste is fine.)

I believe this technique can be used with just about any programming language that compiles to an executable. For example, one could:

- Write a Mal interpreter in Go.

- Modify your Go code to:

- produce a string of Go code and write it to a file;

- compile that resultant file with

go build(by shelling out).

Ideally, there’d be a way to control the Go compiler as a library rather than shelling out, but regardless, this is one way to make a compiler!

With the Mal guide and your ingenuity, you can do it. If I can do it, so can you!

Thanks 🔗

Many thanks to Joel Martin for creating Mal and giving it to the world!